The Wolfe at the Door

“I've looked at life from both sides now. From win and lose and still somehow It's life's illusions, I recall“ - Joni Mitchell

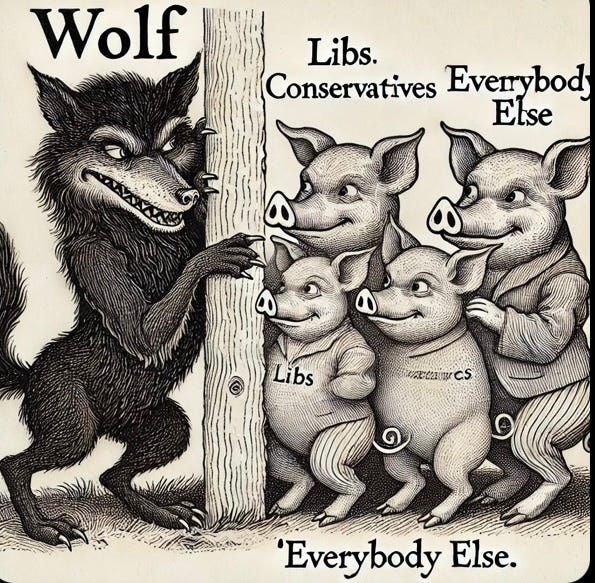

For decades, an insidious nostalgia has spread like a plague through America, splintering our collective identity into hideously recognizable fragments. Many people see the other side of the political divide as hateful stereotypes. Surely we are better than that.

Competing visions of what this country was and should be are shouted on cable news, etched on social media feeds, and whispered in the recesses of the dark web. The idealistic fantasies of yesteryear—already dubious in their time—have fractured into distorted tribal illusions, pitting neighbor against neighbor. How did the Age of Enlightenment give way to this age of delusion? And how can a society that no longer agrees on what it sees in plain sight find its way back to reason?

Alternative facts were once a punchline about Orwellian dystopias; now they’ve graduated into an AI-powered circus act, where the truth is the clown. Machine intelligence has been upgraded to psychological witchcraft, a fetid stew of hate-filled fantasy packaged as group-think manipulation on steroids. Kool-aid, my ass.

Misinformation isn’t just a symptom of technology gone awry—it’s a reflection of our collective vulnerabilities. Tribalism, confirmation bias, and an addiction to outrage form the perfect storm for manipulation. AI feeds us narratives tailored to our fears, offering a comforting yet toxic brew of validation. It’s no longer enough to simply teach media literacy; we’re battling an evolutionary tendency to cling to the familiar, the tribal, and the emotionally charged over the rational. Teaching media literacy today feels like teaching raccoons to share trash—it’s noble, but they’ll always go back to what’s shiny and easy to grab. Denial may have more appeal, but change is, was, and always will be inevitable.

Some of us would like to slink away to an idyllic sanctuary of civil sanity and leave the chaos behind. The dream of fleeing to Costa Rica or Italy is tempting—until you realize civility isn’t much use when the plumbing breaks and no one returns your calls. I’ve lived south of the border and on the other side of the Atlantic, where affordable healthcare is a human right, not a profit center. But human nature’s still the same—bureaucratic, capriciously random, and perpetually drowning in paperwork, though the superior coffee and pastries do make the chaos taste better.

The upsurge of post-election whining about leaving for another country has made some small waves, but most people can’t get up the energy to change channels when they misplace the T.V. remote. And, realistically, family is a noble harbor from which few wish to sail. Even if they could afford a boat.

Thomas Wolfe’s book You Can’t Go Home Again claims: “You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood … back home to a young man’s dreams of glory and of fame … back home to places in the country, back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting, but which are changing all the time.” Change, as Wolfe wrote, is inevitable.

America’s current turmoil reflects a deeper “dis-ease” with change. The country’s demographic, economic, and cultural shifts unsettle those who once believed the old systems were everlasting. Clinging to the past is futile whether we choose to acknowledge it or not. The earth beneath our feet is constantly shape-shifting.

Many of us long to return to a kinder, simpler time when things made more sense, at least on a subjective, illusory basis. I often wonder, as a child (1947) of the postwar-WWII boom in America, if things were as great as they seem in retrospect. Was the abuse of women just as common, yet relegated to back pages because the news only aired once a day? Were the “milk carton kids” of the 1980s less a new tragedy and more a grim upgrade—like finding your missing poster on a billboard instead of a tree? Was it really safe to push your primary-school-age children out the door after breakfast and expect them to wander home dirty, tired, hungry, and smiling—albeit fifteen minutes late for dinner?

I started re-reading Huckleberry Finn yesterday. It’s a good primer of our American roots, fiction or not. Some debate the validity of including this distinctly American classic as required reading in schools because of the racial slurs that were part and parcel of 19th-century colloquial speech. Hell, the N-word was common in the 1950s even in states that won the Civil War. At least most educated (white) people frowned when they heard it. The irony of it being blasted in hip-hop music seems lost on most, and certainly on those born after the civil rights struggle.

I returned to Huckleberry Finn, Twain’s America—messy, divided, yet deeply human—because it feels as relevant now as ever. The novel’s depiction of race, freedom, and morality forces us to grapple with uncomfortable truths about our past and present. Twain’s characters confront the contradictions of their society head-on, with Huck wrestling between what he’s been taught and what he knows to be right. It’s a lesson we could all learn from today.

Many writers claim Mark Twain’s epic to be the great American novel. I think the country would be a better place if every adult in America took time to read/re-read it one weekend. Maybe after the Super Bowl, when the last chip bowl’s empty and the ads have sold us everything short of a retirement condo on Mars, we’ll have time to think—if we can still find the remote.

We’re all guilty, to some degree, of succumbing to the lure of nostalgia or outrage. It’s human nature to seek refuge in the familiar or rail against the unfamiliar. But the world isn’t going backward, and neither can we. If we want a kinder, simpler time, we must build it—not in imitation of an illusory past, but in recognition of our flawed, complicated present.

This requires effort: learning to think critically, confronting uncomfortable truths, and rejecting the easy answers. It’s not glamorous work, but it’s the only way to bridge the chasm between reality and fantasy. America, for all its faults, has always been more an idea(l) than a “shining city on the hill.” Mirages don’t just appear in the desert. Our challenge is to embrace that flux with courage and clarity, rather than retreating into the illusions of yesterday. Between the Super Bowl and the NBA Finals, when a large segment of the population will be at loose ends, maybe we can remember what the promise of America was—and begin to decide what it will be. Unless, of course, NASCAR season starts us going in circles again.

Dante, we are at squaw lake on the Colorado River north of Yuma. So paddling, and it’s beautiful and warm, so no snow here.

Dante, such true thoughts!! Very thought provoking!